Low Wing Airplane Maneuver Tips - Steep Spiral

Intro

- Personally, I find the Steep Spiral to be one of the most challenging maneuvers.

- After plenty of trial and error in X-Plane, I’ve finally had a bit of a breakthrough.

- I’ve put together some insights and tips that I believe will make your training much more effective.

Disclaimer

⚠️ This is for educational and entertainment purposes only. I am not a certified flight instructor (CFI). Do not use this as a substitute for professional flight training. Always consult a CFI and follow your aircraft’s POH. I accept no liability for any actions taken based on this content.

TL;DR

Short on time? Just watch this.

- GS < 80: Use a 30° bank. (Don’t go much lower than this, or the radius gets too wide.)

- GS = 90–95: Stick to the 45° baseline.

- GS > 110: Increase to a 55° bank (But remember, never exceed 60°).

More GS, More Bank, More Back Pressure

Less GS, Less Bank, Less Back Pressure

Why the Steep Spiral is So Challenging

At first, I thought it was just a combination of Turns Around a Point and an Emergency Descent—both maneuvers I practiced during my Private Pilot training. I figured I just had to keep the wingtip on the reference point while descending rapidly, all while staying within bank and airspeed limits. It seemed simple enough in my head, but the reality was quite different.

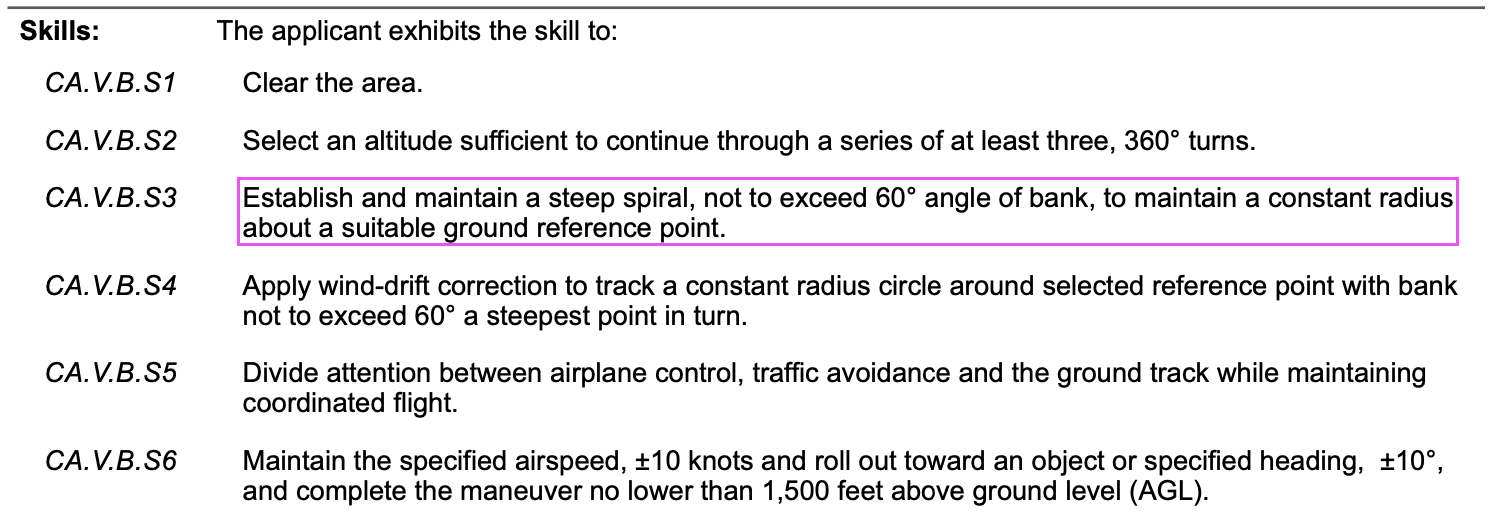

1. How much bank is enough?

The ACS states, “Establish and maintain a steep spiral, not to exceed 60° angle of bank.” But does that mean anything under 60° is fine? Is 45° steep enough? What about 35° or 20°? The real challenge is maintaining a constant radius about a ground reference point. Finding that perfect balance between a specific bank angle and a consistent radius was personally the hardest part for me.

2. What about the airspeed?

The ACS allows a margin of ±10 knots, but ±10 knots from what exactly? Best glide speed? maneuvering speed? or just 90kts? 100kts?

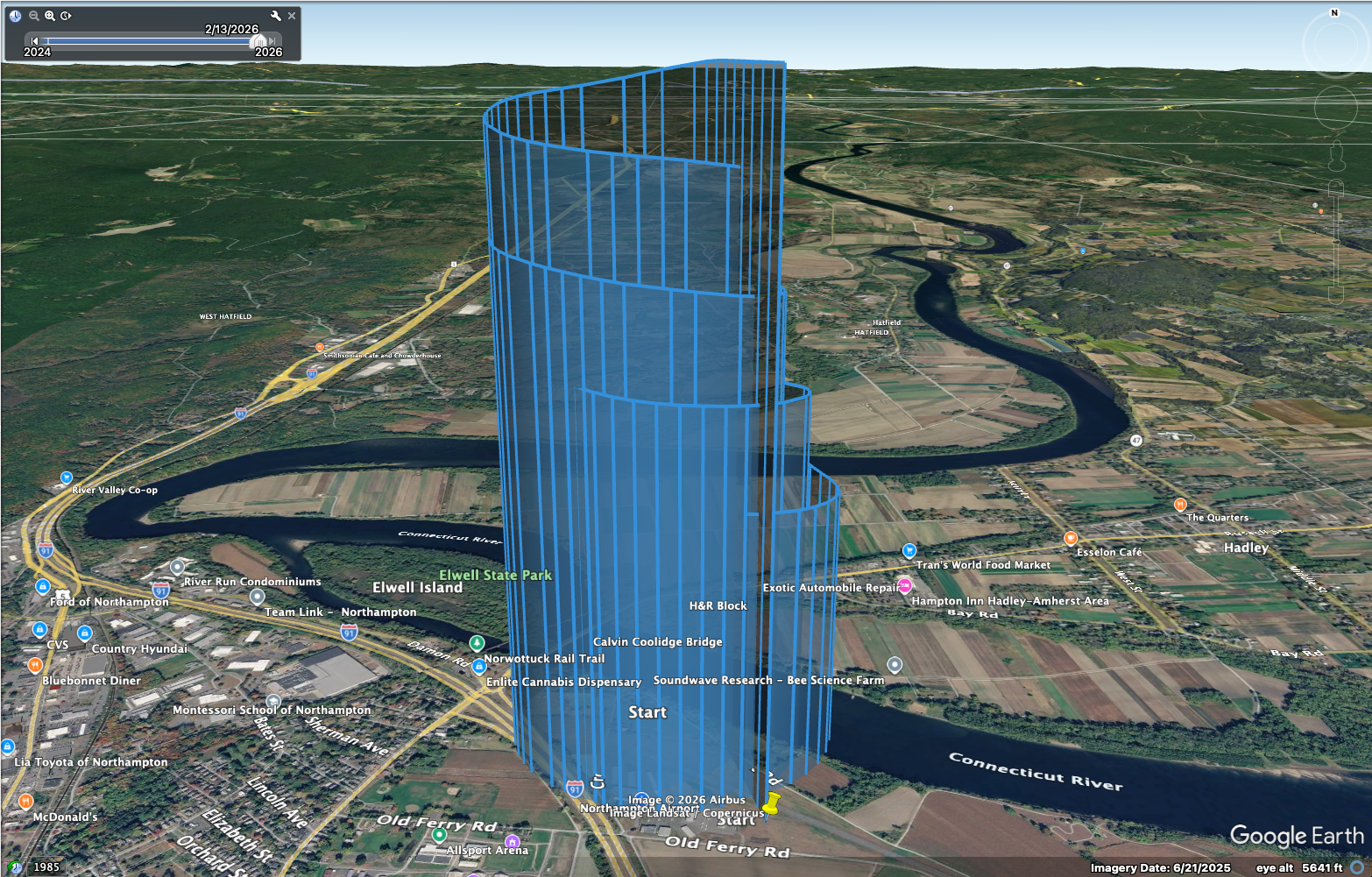

3. Time and Cost

The ACS requires completing the maneuver no lower than 1,500 feet AGL, and since you have to perform three full 360-degree turns, you need plenty of altitude. Even with a conservative estimate of 1,000 feet per turn, you need to start at least at 4,500 feet AGL. My instructor prefers starting at 5,500 feet MSL (airport elevation 120ft MSL) for an extra margin of safety. Because you have to climb so high for every single attempt, this maneuver consumes significantly more time and money compared to others.

4. Different Perspectives (Left vs. Right Seat)

The view of the ground reference point is completely different for the student in the left seat and the instructor in the right. Because of these different angles, it’s hard for the instructor to give precise advice based on exactly what I’m seeing at that moment.

5. The “Low Wing” Struggle

In a low-wing aircraft, the wing often blocks the very ground reference you’re trying to follow. Maintaining visual contact throughout the entire 360-degree turn is much more difficult than it looks.

6. Coriolis Illusion

During a steady steep turn, the fluid in your inner ear stabilizes. If you suddenly move your head to check your GS on the instruments and then look back out at the reference point, it can trigger the Coriolis Illusion.

7. Constantly Shifting Winds

Not only does the wind direction relative to the nose change as you turn, but the wind speed and direction also shift as you descend to lower altitudes. You have to account for these changes constantly.

8. Everything Happens So Fast

As always in aviation, everything happens in a flash. There are so many variables changing at once that if you miss a small correction window, the whole maneuver can fall apart before you know it.

So, How Do We Fix This?

I’ve complained quite a bit, but that’s just because I truly believe the Steep Spiral is one of the trickiest maneuvers out there. At the end of the day, the goal is to find the “sweet spot” for bank angle and airspeed, while figuring out how to handle wind correction. I went through a lot of trial and error in X-Plane to find these numbers.

⚠️ Keep in mind, these aren’t absolute values—they will change depending on the situation.

Why I chose 90-95 KIAS (and why Vg might not be ideal)

While some suggest using Best Glide Speed (Vg), I found it a bit risky for this maneuver. In a PA-28-161, Vg is around 73 KIAS. However, at a 60° bank, your stall speed increases by about 41%. If you’re too slow, your stall margin becomes uncomfortably thin. That’s why I prefer 90-95 KIAS (closer to the Va range of 88-111).

- Safety: It provides a much better stall margin, especially when you’re pulling steep banks.

- Stability: The aircraft feels more stable and responsive to control inputs, even if you encounter sudden gusts.

What about the Bank Angle?

Through my practice, I found that 45° is a great baseline—but only if there’s no wind. To maintain a constant radius, you have to adjust based on your Ground Speed (GS):

- Approaching Tailwind: Your GS increases. You need a steeper bank here, or your turn radius will balloon out, taking you away from your reference point.

- Approaching Headwind: Your GS decreases. You need a shallower bank to prevent the circle from “pancaking” or getting too tight.

The Simulation (X-Plane)

Since I can’t just go up and fly 50 times in the real world, I used X-Plane. Initially, I just wanted to see what the ground reference should look like from the cockpit, but I got a little obsessed… and here we are. In the video below, I’ll show you three scenarios:

- Wind Calm: How a constant 45° bank and 90-95 KIAS creates a perfect circle.

- Wind 180@20kts & No Correction: What happens to your circle when you hold a steady 45° bank without accounting for the wind.

- Wind 180@20kts & With Correction: My experimental results on how to achieve that “constant radius” while staying within the 60° ACS limit.

Rule of Thumb (based on GS)

- GS < 80: Use a 30° bank. (Don’t go much lower than this, or the radius gets too wide.)

- GS = 90–95: Stick to the 45° baseline.

- GS > 110: Increase to a 55° bank (But remember, never exceed 60°).

More GS, More Bank, More Back Pressure

Less GS, Less Bank, Less Back Pressure

Why Back Pressure Matters

Wait, why did I mention back pressure? It’s all about maintaining that target airspeed (90-95 KIAS) while your bank angle constantly changes.

When GS increases (Tailwind):

As you increase the bank to keep the radius constant, you lose the vertical component of lift. This causes the nose to drop, and your airspeed starts to bleed upward. To stay within the 90-95 KIAS range, you need to apply more back pressure to hold the pitch.

When GS decreases (Headwind):

As you shallow out the bank, the vertical lift increases. If you keep the same pitch, the nose will rise and your airspeed will drop. To maintain your target speed, you need to relax the elevator—less back pressure (or even a slight forward pressure)—to keep the nose down.

Track Log

It might not be perfect, but it gets the job done.